Combine Publishers, Part 3: Thead Safety

In Parts 1, and 2, you’ve built a custom Publisher, and did your best to cover its rough edges with unit tests. Now it’s finally time to kick back and relax while it does its job, emitting playback progress. Or is it? Of course it will work well in most cases; but what happens if some threading issues are introduced? Let’s find out!

I only ended up digging into this topic after discussing it on Reddit. Credit goes to u/pstmail4757483 for being kind enough to talk me through it.

Getting Started

Combine’s documentation is a bit absent around thread safety, but after some digging it turns out that there are some rules to follow:

- A call to

receive(subscriber:)can come from any thread- “Downstream” calls to Subscriber’s

receive(subscription:),receive(_:), andreceive(completion:)must be serialized (but may be on different threads)- “Upstream” calls to Subscription’s

request(_:)andcancel()must be serialized (but may be on different threads)

Throughout this guide you’ll look at how these rules apply to the PlayheadProgressPublisher type you worked on in previous parts of the series.

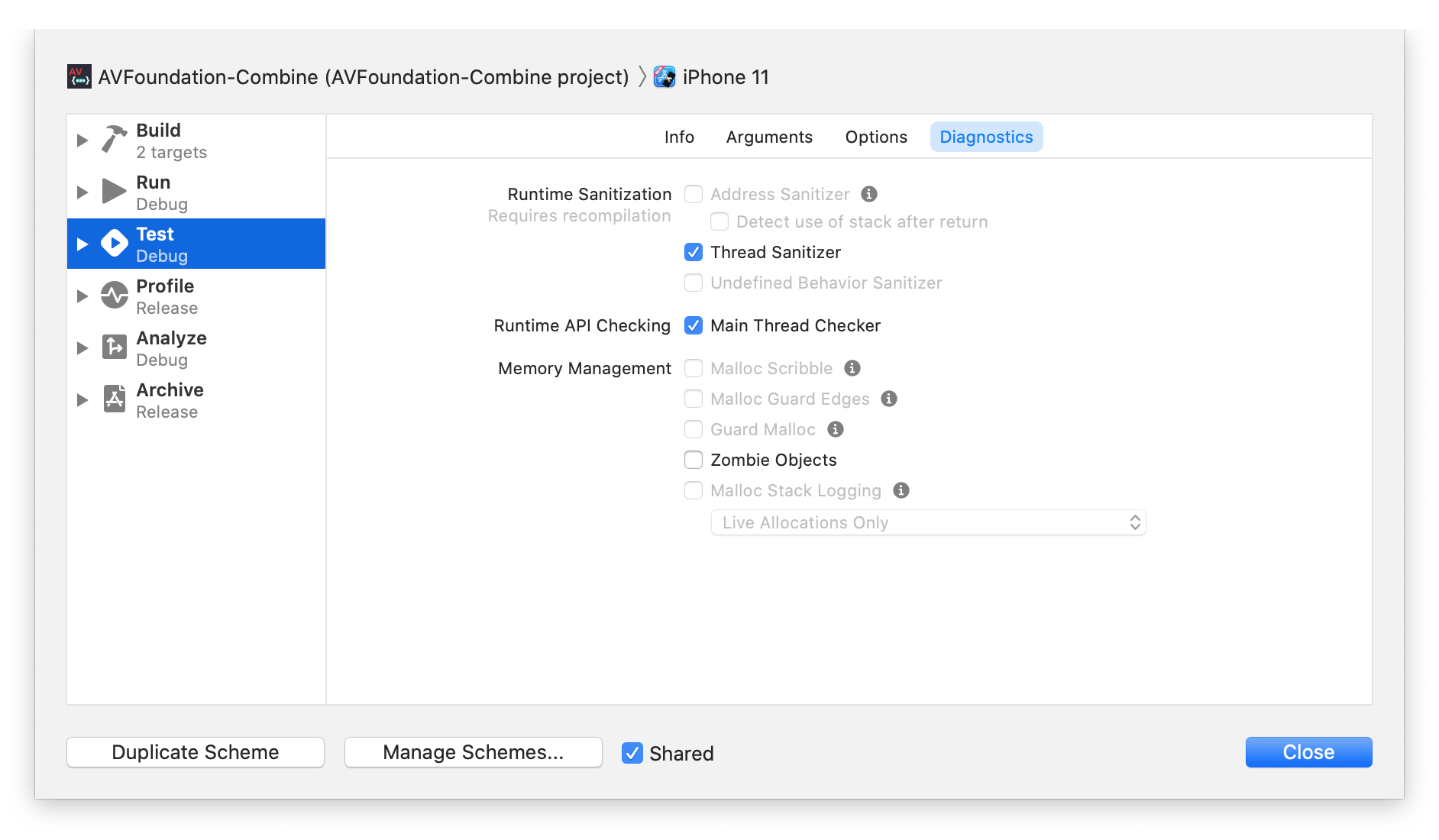

Before going any further, enable Thread Sanitizer in your test target. Whenever you run into concurrency bugs, it will highlight them for you. You can enable it in the scheme editor:

Receiving Demand

Let’s start with the most obvious scenario: the Publisher’s request(_:) method is called anytime to request more values. As noted in Rule #3 above, this call can come from any thread, so it’s worth examining. You’ll start by extracting parts of it into separate methods so it can be changed easier:

func request(_ demand: Subscribers.Demand) {

processDemand(demand)

}

private func processDemand(_ demand: Subscribers.Demand) {

requested += demand

guard timeObserverToken == nil, requested > .none else { return }

let interval = CMTime(seconds: self.interval, preferredTimescale: CMTimeScale(NSEC_PER_SEC))

timeObserverToken = player.addPeriodicTimeObserver(forInterval: interval, queue: DispatchQueue.main) { [weak self] time in

self?.sendValue(time)

}

}

private func sendValue(_ time: CMTime) {

guard let subscriber = subscriber, requested > .none else { return }

requested -= .max(1)

let newDemand = subscriber.receive(time.seconds)

requested += newDemand

}

Looking at the very first line of processDemand(_:), it’s becoming clearer how it could be the subject of race conditions: it updates the requested property. If this method is called multiple times from separate threads, some updates might be overwritten.

You could simulate this scenario with the following unit test (click for the source code of TestSubscriber if you need a refresher):

func testWhenValuesAreRequestedFromMultipleThreads_RequestsAreSerialized() {

// given

let requestCount = 1000

let expectation = XCTestExpectation(description: "\(requestCount) values should be received")

expectation.expectedFulfillmentCount = requestCount

let subscriber = TestSubscriber<TimeInterval>(demand: 0) { _ in

expectation.fulfill()

return 0

}

sut.subscribe(subscriber)

let group = DispatchGroup()

for _ in 0..<requestCount {

group.enter()

DispatchQueue.global().async {

subscriber.startRequestingValues(1)

group.leave()

}

}

_ = group.wait(timeout: DispatchTime.now() + 5)

// when

(1...requestCount).map { TimeInterval($0) }.forEach { time in

player.updateClosure?(CMTime(seconds: time, preferredTimescale: CMTimeScale(NSEC_PER_SEC)))

}

// then

wait(for: [expectation], timeout: 1)

}

The test will request 1000 values, all from different threads. Then, 1000 mock values are served. If the Publisher worked correctly, it would be reasonable to expect that all 1000 requests are registered, and the values are served.

In reality however, it will mostly work, but sometimes it won’t: since access to the Subscription’s requested property is not protected in any way, the demand may end up being less than 1000 due to data races.

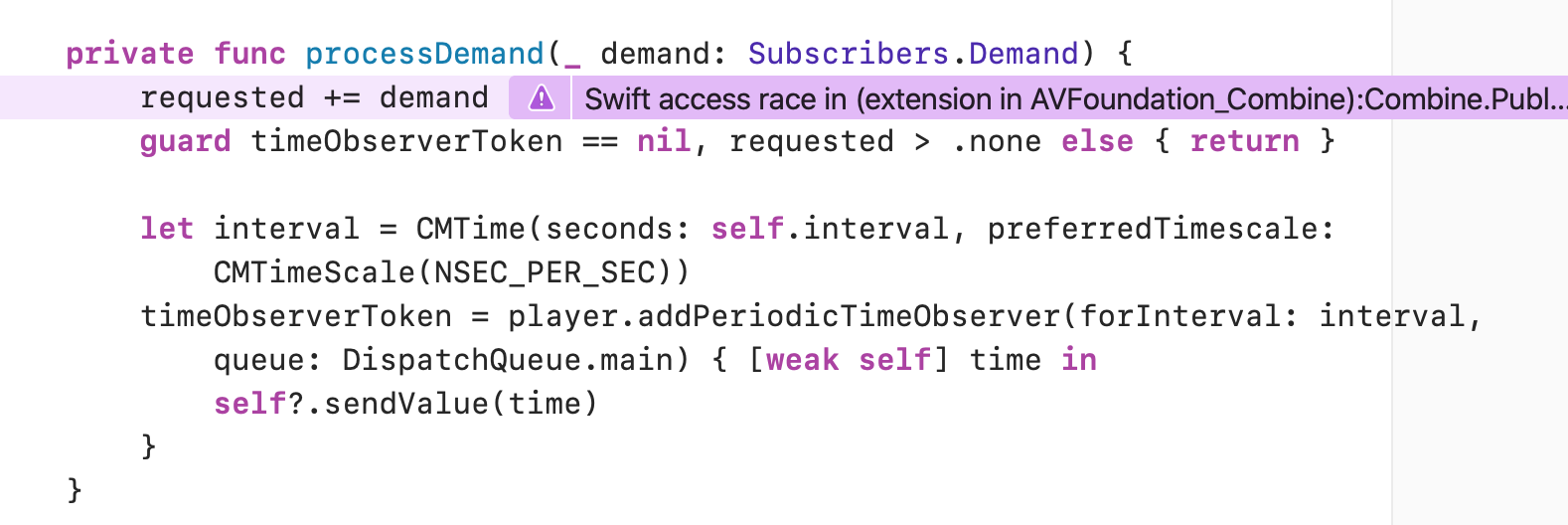

Running this test with the Thread Sanitizer enabled will immediately flag the issue:

A possible way to solve this issue is to introduce a serial queue to make sure that demand requests are handled in order:

private final class PlayheadProgressSubscription<S: Subscriber>: Subscription where S.Input == TimeInterval {

private let queue = DispatchQueue(label: "PlayheadProgressSubscription.serial")

...

func request(_ demand: Subscribers.Demand) {

queue.sync {

processDemand(demand)

}

}

...

}

If you re-run the test, you’ll notice that the data race warning is gone.

Sending Values

One issue down, but you’re not quite done yet. If you recall, whenever a value is emitted, the Subscriber gets a chance to update the demand.

private func sendValue(_ time: CMTime) {

guard let subscriber = subscriber, requested > .none else { return }

requested -= .max(1)

let newDemand = subscriber.receive(time.seconds)

requested += newDemand

}

Progress updates from AVPlayer are currently served on the main thread, which means that requested is still unsafe: it can be updated from the private serial queue, and the main thread as well. To catch that, let’s create another test:

func testWhenRequestAndDemandUpdateAreSentFromDifferentThreads_UpdatesAreSerialized() {

// given

let expectation = XCTestExpectation(description: "1 value should be received")

expectation.expectedFulfillmentCount = 1

let subscriber = TestSubscriber<TimeInterval>(demand: 0) { _ in

expectation.fulfill()

return 0

}

sut.subscribe(subscriber)

subscriber.startRequestingValues(1)

let group = DispatchGroup()

group.enter()

DispatchQueue.global().async {

subscriber.startRequestingValues(1)

group.leave()

}

player.updateClosure?(CMTime(seconds: TimeInterval(1), preferredTimescale: CMTimeScale(NSEC_PER_SEC)))

_ = group.wait(timeout: DispatchTime.now() + 5)

// then

wait(for: [expectation], timeout: 1)

}

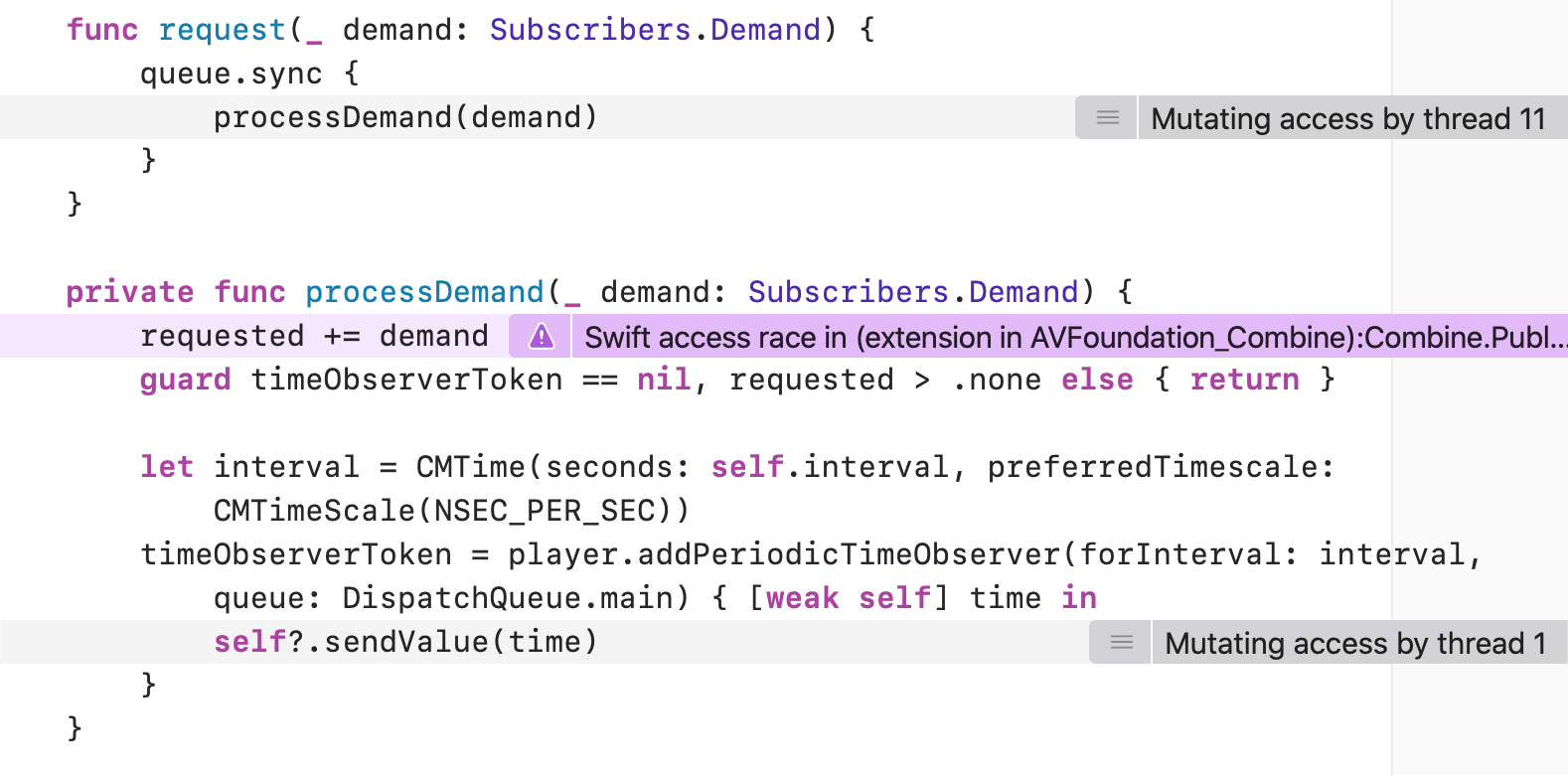

As a logic test, this is not super useful, but it creates just enough chaos to simulate a race condition: a demand is dispatched from a global queue, and a mock value is sent from the main thread. Running it will trigger Thread Sanitizer most of the time:

You’ll notice that both Thread 1 and 11 are attempting to modify requested, confirming a race condition. At first it might seem like a good idea to use the same queue in the sendValue(_:) method:

private func sendValue(_ time: CMTime) {

queue.sync {

guard let subscriber = subscriber, requested > .none else { return }

requested -= .max(1)

let newDemand = subscriber.receive(time.seconds)

requested += newDemand

}

}

However doing this can produce a deadlock. Again, this is a contrived example, but let’s suppose that the Subscriber invokes request(_:) immediately upon receiving a value:

func receive(_ input: T) -> Subscribers.Demand {

subscription?.request(.max(1))

return .none

}

This will produce a deadlock, as the method will have to wait until the queue (currently also used for delvering the value) is freed up. A quick fix-it is to use queue.async instead of sync, to prevent the queues from blocking.

Instead of going async, another option is to use a recursive lock: NSRecursiveLock provides exclusive access, but also prevents simultaneous requests (like the one described above) from deadlocking. Also, it allows the implementation to remain synchronous.

To adopt this locking behavior, let’s introduce a few changes to PlayheadProgressSubscriber:

private final class PlayheadProgressSubscription<S: Subscriber>: Subscription where S.Input == TimeInterval {

...

private let lock = NSRecursiveLock()

private func withLock(_ operation: () -> Void) {

lock.lock()

defer { lock.unlock() }

operation()

}

...

}

withLock(_:) will save you from doing the lock/unlock dance each time. Now you can update request(_:) and sendValue(_:):

func request(_ demand: Subscribers.Demand) {

withLock {

processDemand(demand)

}

}

private func sendValue(_ time: CMTime) {

withLock {

guard let subscriber = subscriber, requested > .none else { return }

requested -= .max(1)

let newDemand = subscriber.receive(time.seconds)

requested += newDemand

}

}

If you run the test suite now, you’ll see that no data races occur.

Cancellation

The thread safety rules outlined above mention that calls to cancel() should also be serialized. In fact, the documentation for Subscription also mentions that cancelling must be thread-safe

Let’s look at the implementation to see why:

private func sendValue(_ time: CMTime) {

guard let subscriber = subscriber, requested > .none else { return }

requested -= .max(1)

let newDemand = subscriber.receive(time.seconds)

requested += newDemand

}

func cancel() {

if let timeObserverToken = timeObserverToken {

player.removeTimeObserver(timeObserverToken)

}

timeObserverToken = nil

subscriber = nil

}

Notice, how the subscriber is modified in cancel(), while also read in sendValue(_:). There’s no good way to consistently reproduce it, but this setup also may also result in a race condition. So just to be on the safe side, let’s follow the rules, and apply locking on cancellation as well.

func cancel() {

withLock {

if let timeObserverToken = timeObserverToken {

player.removeTimeObserver(timeObserverToken)

}

timeObserverToken = nil

subscriber = nil

}

}

Conclusion

With the locks in place, you ensured that that processDemand(_:), sendValue(_:), and cancel() cannot run at the same time, thus making sure that requested, and subscriber is only accessed by one thread.

As you can see, it’s not easy to come up with reliable tests for race conditions; but just because you can’t reproduce them, it doesn’t mean that they can’t surprise you with obscure, hard to debug crashes in production. It’s better to be on the safe side, and apply defensive locking.

To finish up, I’d like to highlight a few resources I found useful while researching:

For more details, feel free to check out the full project on GitHub. Also, please send any questions or feedback on Twitter. This post wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for reader feedback. Thank you for reading!